Untold Histories: A Parallel Household

May 3, 2020

By Caitlin Henningsen, Associate Museum Educator for College and University Programs

Tucked away on the wainscotting in The Frick Collection’s West Gallery are five small mother-of-pearl buttons inscribed with words such as “BUTLER” and “PANTRY.” They belong to an elaborate annunciator, or call bell, system that once blanketed the Frick mansion, connecting the family and its guests to a staff of about thirty that kept the home running. At the push of a button, from the center of his grand gallery, Henry Clay Frick could summon his personal valet, secretary (“SEC’Y”), or housekeeper (“HSKPR”). Though today J.M.W. Turner’s magnificent Harbor of Dieppe and Cologne tend to overshadow these intentionally discreet panels, they are nonetheless fascinating traces of life at 1 East 70th Street when it was a private home, from 1914–31.

Looking at these buttons, I began to wonder just who responded to each bell. Members of the Frick family’s staff are identified by their roles, but what were their names? What were their lives like? Almost nothing has been published about this aspect of the house’s history, so, working with Archives and Education staff, I began a research project to bring to life less visible histories of this remarkable home.

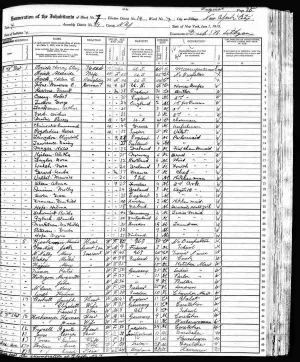

The Frick residence, completed in 1914 by the firm Carrère and Hastings, is a late example of the grand homes built for New York City’s wealthy elite during the Gilded Age. Many of these mansions boasted cavernous ballrooms, picture galleries, bowling alleys, and pools, as well as modern conveniences like elevators, washing machines, and refrigerators. Yet no matter how technologically sophisticated, they all depended on enormous staffs of domestic workers. The 1915 New York State Census entry for 1 East 70th Street (below) provides a glimpse of this parallel household, made up of maids, butlers, footmen, laundresses, and cooks.

Let’s look more closely at this document. Column three lists the “head of household,” industrialist Henry Clay Frick (line 1), followed by his wife Adelaide Childs Frick and daughter Helen. The next twenty-seven people are identified as “servants,” who lived on-site in the basement and on the third floor. (According to employment records held in the Frick Family Papers in the Frick Archives, the staff working at the mansion in 1915 actually numbered over thirty.) The census registers demographic information about their age, sex, race, “nativity” or place of birth, citizenship status, number of years in the United States, and occupation. The final column indicates each individual’s class—“W” for workers, “Emp” for employers (Frick is so designated in line 1), and “x” if the individual was “not engaged in gainful occupation,” such as Adelaide and Helen. The long column of “W’s” at the far right of the document is a testament to the amount of labor this “comfortable…simple…not ostentatious” home required.

Heading the list of employees are the most senior members of the household staff: housekeeper Minerva Stone and butler Frank Kearns. Stone was a widow from Massachusetts who held considerable power at 1 East 70th Street, supervising staff, keeping the household purse, and paying the salaries of everyone from the butler to the third laundress. Frank Kearns, meanwhile, was one of a steady stream of butlers and footmen, whom he oversaw. The fact that Kearns and his staff were English seems to reflect an upper-class preference for Britons in positions requiring significant public contact.

In fact, most of the Fricks’ staff were born outside of the United States (see the countries listed in column seven), consistent with the overall makeup of the domestic labor pool in New York City at the time. More surprising, given the conventional notion of the Irish “Bridget,” or maid, in turn-of-the-century American homes, is the relatively small number of immigrants from Ireland; many more of the Fricks’ domestic staff hailed from Scandinavia, England, and Scotland.

As the listings reveal, the Fricks’ employees were predominantly young and white, a trend confirmed by subsequent state and federal census entries for this home. As far as we know, only one African American person worked for the Fricks at their Upper East Side residence, a man named Percy Martin, who is identified in the 1915 census as a “choreman” and was one of the longest-serving members of the Fricks’ staff.

Today the call buttons in the West Gallery are some of the only elements in the museum’s public spaces that hint at the presence of the parallel household that once existed at 1 East 70th Street. The invisibility of this legacy today mirrors the unobtrusive roles the staff were meant to play, on the third floor and in the basement—as out of view to today’s visitors as they were to callers at the time.

In future entries, we’ll meet more of the people who contributed to the running and making of the Frick mansion and explore topics like the call bell system in greater detail. Research for this project is still underway, so if you have any stories, photos, or documents to share related to individuals who worked at 1 East 70th Street, please don’t hesitate to contact me at academic@frick.org.

Thanks are due to the following researchers, who made great contributions to this project: Hannah Diamond, Education Manager for Professional Learning at the Museum of the City of New York (former Ayesha Bulchandani Graduate Intern), and Julia Butterfield and Zoë Hopkins, Special Projects Interns; and to The Frick Collection’s outstanding Archives staff: Sally Brazil, Susan Chore, Elizabeth Kobert, and Julie Ludwig.

This blog post is part of Untold Histories, an ongoing research project into life behind the scenes at the Frick mansion when it was a private home. Discover more exciting education programs and digital initiatives at Frick Connections.