The First Handbook: "Paintings in the Collection of Henry Clay Frick"

November 30, 2022

By Julie Ludwig, Archivist

When The Frick Collection opened eighty-seven years ago, on December 16, 1935, Henry Clay Frick’s art treasures were unveiled to the curious masses, eager to see the once private collection and home. The opening, however, was not the first time the works of art and interiors at Frick’s New York City residence were seen by members of the public. From 1914 to 1919—the years Frick resided at 1 East 70th Street until his death—he received numerous inquiries to visit the house and view his collection.

The applicants cut a wide swath of backgrounds, vocations, and positions, including art historians and dealers, museum professionals, students, society women, civic and cultural organizations, business associates, diplomats, and members of the military. Unless the house was closed for the summer season (approximately May through October each year) or if renovations or installations were underway, Frick generally approved these requests, presaging his desire to share his collection with the wider public.

Recent research in The Frick Collection and Frick Art Reference Library Archives has deepened our understanding of outside visits to 1 East 70th Street prior to the 1935 opening. Documentary evidence indicates that visits were appointed either by Alice Braddel, Frick’s secretary; Ruth E. Williams, Caretaker of the Gallery from 1915–17; or James Howard Bridge, an author employed by Frick in a somewhat vague position beginning in 1912. (Bridge would later go on to describe himself as the collection’s curator, an assertion Helen Clay Frick disputed, leading to a slander and libel lawsuit in the early 1930s.) Visitors were likely led through the gallery by either Williams or Bridge, and all but friends and close associates of the family were probably limited to works on view in the West Gallery and Enamels Room.

Frick no doubt knew the value of educating visitors about the objects they encountered in his collection. In February 1916, the household diary notes the arrival of one hundred copies of a handbook prepared by Bridge. Entitled Paintings in the Collection of Henry Clay Frick (above), it contains reproductions and descriptions of works on display in the principal rooms at the Frick residence.

Explore the handbook in full by flipping through a digital copy.

Each entry contains a two-letter code denoting the room and wall on which the work could be found (e.g. “GS” is Gallery South, “LN” is Library North, etc.). The first work listed hung on the left upon entering, and then paintings are reproduced in clockwise order as they hung around the room. Seven additional paintings are illustrated and described at the end of the volume, followed by a supplemental list of works found in rooms not commonly open to visitors, such as the family’s bedrooms and sitting rooms.

The handbook focuses only on paintings and was published during a period of intense acquisition by Frick. From 1914 to 1916, he purchased more than fifty new paintings—roughly four times the number he had acquired in the preceding three years. This meant the catalog was outdated almost immediately after it was issued (see below). One of the last acquisitions to be included in the 1916 handbook was Bronzino’s Lodovico Capponi; Gainsborough’s Mall in St. James’s Park was purchased only three months after the Bronzino, but too late to be included.

Initial presswork on the handbook was completed by the Andrew W. Kellogg Co. in November 1915, though Bridge continued to make changes over the next few months, possibly to incorporate works newly added to the collection. One thousand copies were printed in January 1916, of which one hundred were bound in morocco leather, with the title stamped in gold leaf on the cover. 102 additional handbooks were bound in early 1919. Bridge continued to work for the family after Henry Clay Frick’s death, coordinating visits and preparing an expanded edition of the handbook around 1925. This version added fourteen paintings to the seventy-five already described in the 1916 edition, including Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid, Frick’s last acquisition before his death.

Explore a full digital copy of the expanded 1925 edition.

According to Bridge, the handbook was created for two purposes: first, for distribution among Frick’s friends and acquaintances, and second, for use by visitors while touring the galleries. Unlike the catalogs of the collection of Frick’s contemporary J. P. Morgan, which are massive tomes issued in several volumes arranged by genre and national school, Frick’s handbook was small, portable, and intentionally not exhaustive. Bridge did have plans to create a more comprehensive two-volume catalog, but this project was never completed. Helen Clay Frick initiated her own catalog of her father’s collection in the late 1920s, the first folio catalog of which was not published until 1949. Eleven more volumes followed between 1949 and 1956.

Nevertheless, the handbook was a singularly useful reference for visitors in its day, and it still assists us in understanding the early arrangement of works at 1 East 70th Street, even if the information is limited and does not include furniture, sculpture, or decorative art. It is, in fact, the most complete documentation of its kind produced during Frick’s lifetime: An estate inventory prepared in the year after his death lists contents only by room, and the first interior photographs of the house were not taken until 1927, by which point some works had been moved.

As the Frick prepares for the return to its historic buildings following the renovation and enhancement project, the 1916 handbook furthers our understanding of the permanent collection and its presentation at different stages in the institution’s history. This resource deepens our appreciation of the fact that—even before the building’s conversion to a museum—the Frick’s appearance was in constant flux. The handbook thus offers a snapshot, one of the only ones we have, of what visitors may have seen on the walls of 1 East 70th Street when it was still a private home.

Explore the Complete Digitized Handbooks

Transcript

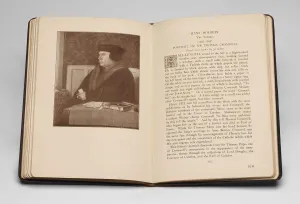

Image #1: Entry for Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell

Hans Holbein

The Younger

(1497–1543)

Portrait of Sir Thomas Cromwell

Panel, 24 1/2 inches by 30 inches

Half-length, seated to the left in a high-backed wooden seat, three-quarter face, looking toward a window, with a small table beneath it covered with a Turkish cloth, on which papers are placed. He is dressed in black surcoat with deep fur collar; black cap on bushy hair which almost covers his ears and falls on the back of his neck. Clean-shaven face; holds a paper in his left hand, on the first finger of which is a heavy signet ring. On the table are pen and ink, a richly-bound book with jeweled clasps, and several papers, on one of which is inscribed: “To our trusty and right well-beloued Thomas Cromwell Maister of our Jewel-house.” On a second paper the word “Counseilor” can be deciphered. A Latin eulogy on a scroll was added after Cromwell’s death, but later removed.

Henry VIII. sent his councillors to the block with the same indifference that he beheaded his wives; and Cromwell, the plebeian antithesis of the aristocratic More, came to the same fateful end at the Tower of London. Shakespeare makes Cardinal Wolsey charge Cromwell “to fling away ambition; by this fell the angels.” And by this fell Thomas Cromwell, who began life as the son of a farrier and died as Earl of Essex. While Sir Thomas More lost his head because he opposed the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, Cromwell met the same fate through his encouragement of Henry’s love for the new queen and the resentment of the Catholic nobles which this and cognate acts engendered.

This historic portrait descends from Sir Thomas Pope, one of Cromwell’s instruments in the suppression of the monasteries; thence through the collections of Lord Douglas, the Countess of Caledon, and the Earl of Caledon.

107

HN