Ars Longa: The Turbulent Fate of Raphael's Baronci Altarpiece

February 15, 2022

By Sarah Bigler, Photoarchivist

The resources of the Frick Art Reference Library’s Photoarchive allow us to study works of art as objects with complicated histories, from little-known family portraits to paintings by major artists. One such work is the first recorded commission of the High Renaissance master Raphael, the Baronci Altarpiece of 1500–01. A complex composition (below) depicting a saint’s coronation, the Devil, the Virgin Mary, God the Father, and other figures in a fictive architectural space, the altarpiece remained undisturbed in its home in the church of Sant’Agostino in Umbria, Italy, for nearly three hundred years, until it was severely damaged in an earthquake in September 1789.

Over the next few decades, the surviving pieces of the altarpiece were caught up in the chaos of the Napoleonic Wars and were ultimately split up. Using reproductions found in the Photoarchive, we can learn more about the destroyed altarpiece as well as trace surviving fragments over the centuries, from the chapel in Sant’Agostino to their current homes in European museum collections.

The Baronci Altarpiece was commissioned from Raphael on December 10, 1500, by local wool merchant Andrea di Tommaso Baronci for his family’s chapel in the church of Sant’Agostino in Città di Castello, in central Italy, where Raphael was based in his early career. Delivered on September 13, 1501, the altarpiece celebrated the coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, a thirteenth-century Augustinian monk and mystic whose cult became popular in Italy in the 1400s. Having worked as a peacemaker during a time of civil unrest and religious conflict, he later came to symbolize the reunification of the Catholic Church. Nicholas of Tolentino was also known as a plague saint; an outbreak in Città di Castello may explain Raphael’s choice of subject matter.

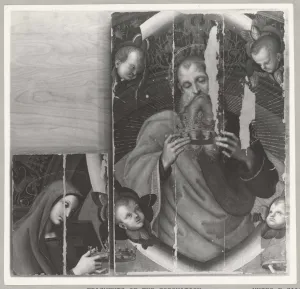

The Photoarchive’s image of a reconstruction of the altarpiece (above) captures the original composition. Saint Nicholas is depicted in an archway flanked by angels, with the Devil splayed out at his feet. Above him, the Virgin and Saint Augustine (the patron saint of the church for which the altarpiece was destined) hover beneath the figure of God the Father surrounded by putti. The geometric harmony of the composition is typical of Raphael’s style. In multiple preparatory studies held in the Photoarchive (below), we can see the artist working out the carefully composed relationships between individual figures, their groupings, and the architectural setting.

The completed altarpiece stood in the Baronci family chapel for generations, until a devastating earthquake hit the region in 1789, almost entirely destroying Raphael’s original work. A copy (below) was commissioned to replace the original from Baroque artist Ermenegildo Costantini. Completed in 1791, Costantini’s version resembles Raphael’s composition, minus the upper register with the figures of God the Father, the Virgin, and Saint Augustine and with a simplified architectural setting.

After the 1789 earthquake, the three undamaged portions of Raphael’s altarpiece were cut out and purchased by Pope Pius VI. The fragments were brought to Rome around 1791, where they were restored and displayed at the Vatican, the site of many of the artist’s prestigious later commissions.

Just a few years later, in 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte, then a general in the French Revolutionary Army, arrived with his troops in Rome, seizing the fragments of the Baronci Altarpiece along with many other treasures of the Vatican. Iconic works such as the Laocoön and the Apollo Belvedere were taken from Italy as spoils and brought back to Paris to fill the Musée Napoléon, as the Louvre was known from 1803 to 1815. So many important works of art were looted that a French song was written in 1798 to celebrate the arrival of masterpieces from Italy, with the refrain “Rome is no more in Rome, it is all in Paris.”

The fragments of the Baronci Altarpiece seized by the French were first taken to the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. From there the three segments were separated, and the story gets murkier. According to Photoarchive documentation, the fragments of God the Father and the Virgin (below) were taken to Naples in 1799 along with other works of art that had been looted from collections in the city. By 1802, they were installed in the Palazzo Francavilla, which later became part of the Pinacoteca del Museo Nazionale in Naples, where they remain today.

As noted in the Photoarchive records, the Head of an Angel fragment (below, right) disappeared for several decades, emerging again in 1821 at a sale in Florence, where it was purchased by Count Paolo Tosio of Brescia. The count bequeathed it, along with his other collections, to the Pinacoteca Comunale Tosio, Brescia, in 1846.

The history of the final surviving piece, the Angel Holding a Phylactery (below, left), is even more mysterious. It seems that the fragment was taken to Paris along with so many other masterpieces of Italian and Netherlandish art in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, though it never became part of the national collections at the Musée Napoléon. Disappearing around 1798, Angel Holding a Phylactery was considered lost for more than a century, until it reappeared in 1981 in a French private collection and was subsequently sold to the Musée du Louvre.

Today, as we encounter what remains of the Baronci Altarpiece and other works of art in museum collections, their intricate stories of loss, alteration, and plunder are often obscured. Even for an artist as exhaustively studied as Raphael, open questions can remain about a work’s origins and permutations over time. The Photoarchive makes it possible for scholars to fill in many of these gaps. Using reproductions held in our collection, we are able to recreate a full visual history of Raphael’s altarpiece, which fell victim to both natural disaster and political upheaval and which survives only in fragments. The vast resources of the Photoarchive help preserve this work and others that suffered similar fates, extending our understanding and appreciation of countless treasures that were nearly lost to history.

The Photoarchive is the founding collection of the Frick Art Reference Library, comprising reproductions of more than one million works of art. Ars Longa is a blog series exploring the documentation of lost, altered, and destroyed works—as well as those in private collections or otherwise not easily accessible—highlighting the Photoarchive as an invaluable resource for the public.

Sources

Béguin, Sylvie. “Un nouveau Raphaël : un ange du retable de Saint Nicolas de Tolentino,” in La Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France (1982), 99–115.

McClellan, Andrew. Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-Century Paris. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Musée du Louvre website, accessed January 2022.