One Hundred Years at the Library: Surrealism in Print

October 19, 2022

By Stephen J. Bury, Andrew W. Mellon Chief Librarian

In celebration of the centennial of the Frick Art Reference Library, peek into the past one hundred years of the library’s remarkable history through important places, people, and objects from the collections. The objects featured are included in the commemorative publication One Hundred Objects in the Frick Art Reference Library and are available for consultation in our reading room.

In this third entry, we look at examples from the library’s Surrealist exhibition catalogs.

The founding of the Frick Art Reference Library in the 1920s coincided with major events in modern art, including the rise of Surrealism in Paris. The first Surrealist manifesto was published in 1924 by one of the movement’s leaders, André Breton. Along with the Dada art movement, which was founded in Zurich, Switzerland, Surrealism opposed the established social and political order that its adherents blamed for the devastations of World War One. Unlike Dadaism, which embraced nonsense and the absurd, Surrealism was interested in viewing reality through dreams and the unconscious mind—the realm of the “super-real,” or the surreal.

Both a literary and artistic movement, Surrealism and its history are inextricably bound up with the print format. Its exhibitions, gallery affiliations, bookshops, manifestos, and journals all produced printed materials, each permutation of which is reflected in the library’s holdings. Through these items, visitors to the library can track the progression of the influential movement as well as the many internal tensions that arose within it.

To collect the most up-to-the-minute art historical materials, the Frick Art Reference Library had an agent in Paris, Clotilde Brière-Misme, who supplied it with catalogs from contemporary art exhibitions and other printed works. These included catalogs from the Galerie Surréaliste, which opened at 16 rue Jacques-Callot in March 1926. The gallery was perpetually in bad financial straits, which one can sense by the cheap format of its catalogs.

Surrealist and other exhibition catalogs list the works on view in a gallery at a particular time, so they prove useful for researchers of provenance (the record of ownership of works of art), a core interest of the Frick Art Reference Library’s community of scholars. The first Galerie Surréaliste exhibition displayed twenty-four works by artist Man Ray alongside sixty-two figures from Easter Island. The library has the catalog from the show (above), which caused a scandal due to the rather phallic Easter Island figurine that featured prominently in the gallery window and on the catalog’s cover.

The nascent Surrealist movement also took a great deal of inspiration from the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, who developed metaphysical art in the years leading up to World War One. André Breton admired De Chirico’s work and bought his 1914 painting Le Cerveau de l’enfant (The Child’s Brain) from Paul Guillaume, an important modern art dealer, keeping the canvas until 1964.

However, in the 1920s, De Chirico followed a trend called the “return to order,” which rejected avant-garde art in favor of more classical styles and iconography. The Surrealists disliked this, and an eventual split was inevitable. Shown above, the catalog of the De Chirico exhibition at the Galerie Surréaliste is pointedly titled Oeuvres anciennes de George de Chirico (Older Works by Giorgio de Chirico), emphasizing the movement’s interest only in his metaphysical style.

Located at 6 rue de Clichy, the Librairie José Corti was another haunt of the Parisian Surrealists. The bookshop specialized in Surrealist literature and film, and Corti also founded, in 1925, the publishing house Éditions Surréalistes, which produced the Man Ray and De Chirico catalogs for the Galerie Surréaliste.

The Frick Art Reference Library has two Corti bookshop catalogs, from 1930 and 1931, as well as an exhibition catalog from a show held at the shop in March 1930. The catalog (above) includes a text by leading Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, “La Peinture au défi” (“The Challenge of Painting”) and lists works in the exhibition—the theme of which was collage, a favorite genre of both Dada and Surrealist artists. Major artists represented include the Cubists Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Pablo Picasso; Dadaists Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, and Francis Picabia; and Surrealists Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Joan Miró, and Yves Tanguy.

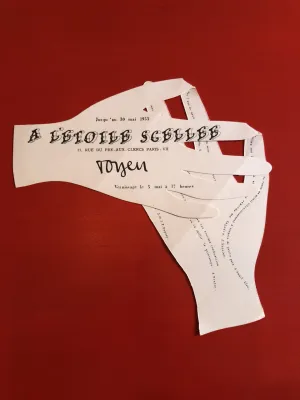

Next, from 1937–38, André Breton was involved with the Galerie Gradiva; no exhibition catalogs survive, if any indeed existed, and documentation is poor. The third gallery with which Breton was affiliated was À L’Étoile scellée. The gallery’s name translates to “At the Sealed Star” or, phonetically, Ah, les toiles, c’est laid (“Oh, how the canvases are ugly”), appealing to the Surrealists’ love of word games. The Frick Art Reference Library holds seventeen out of an estimated twenty-six catalogs from the À L’Étoile scellée gallery, more than any other library collection.

At À L’Étoile scellée, Breton served as an advisor alongside critic Charles Estienne, who championed abstraction, which led to some tension among the purist Surrealists; Man Ray deliberately called his 1956 exhibition at the gallery Non-Abstractions. Breton showed works by his friends, including Meret Oppenheim and Toyen, whose expressive May 1953 catalog is shown above. Like all of the Surrealist galleries, À L’Étoile scellée ran into financial difficulties, and it was closed abruptly in June 1956 by its patron Sophie Babet.

Breton’s involvement with the Galerie La Dragonne, run by Nina Dausset at 19 rue de Dragon, was even more problematic. Although the gallery organized a Surrealist center, the Solution surréaliste, this lasted only one year. In 1948, Breton exhibited cadavre exquis (“exquisite corpse”) drawings, which were a favorite game of Surrealists in which successive players would add to a composite sketch without being able to see previous additions; see the example above. Shortly after, Breton and Dausset had a rupture, and she went on to show artists far from the Surrealist canon, including Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Jean-Paul Riopelle. Breton seems never to have understood the motto of not biting the hands that feed you.

The Surrealist movement in Paris was avant-garde and turbulent, and its leader, André Breton, was as divisive as he was visionary. This history is inextricable from the movement’s art, literature, and exhibitions, which materials preserved at the Frick Art Reference Library—in some cases the only copies that survive—help us chart. These items correspond to the early days of the library, which over the past hundred years has enabled the study of a wide breadth of art history, from the fourth century to the mid-1900s, offering the public an almost “surreal” journey through time.

Learn more about the history and offerings of the Frick Art Reference Library at frick.org/library. Discover all one hundred objects in One Hundred Objects in the Frick Art Reference Library. To explore more content celebrating the library’s centennial, watch our video series on YouTube, subscribe to our e-news, and follow us on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.

One Hundred Years at the Library is supported in part by Virginia and Randall Barbato.