Portrait Drawings

Portrait Drawings by Van Dyck's Contemporaries

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Hendrick van Thulden, ca. 1615–16

Black chalk, on buff paper

14 3/4 × 10 3/8 in. (37.4 × 26.2 cm)

The British Museum, London

This drawing was attributed to Van Dyck until recognized as a preparatory sketch for a portrait of the theologian Hendrick van Thulden by Peter Paul Rubens. Dated around the time Van Dyck entered the studio of Rubens in the mid-1610s, it must be the type of sketch the younger artist saw his master make in connection with portraits and which he followed in his own studio. It is very similar to many of Van Dyck’s portrait studies.

Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678)

Catharina Behagel, 1635 or shortly before

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk

11 1/2 × 7 3/4 in. (29.2 × 19.7 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

The cartouche of the blue mount made for the drawing by the eighteenth-century French collector Pierre-Jean Mariette attributes the sheet to Van Dyck. The focus on the pose and costume of the lady, rather than on her face, is indeed comparable to many of Van Dyck’s surviving chalk studies for portraits from the 1630s. However, the more regular, controlled style points to Van Dyck’s great contemporary Jacob Jordaens, who made the drawing in preparation for a painted portrait of the wife of a wealthy Antwerp merchant.

Attributed to Jan Cossiers (1600–1671)

Head Study of a Man Looking Left, ca. 1630–50 (?)

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on buff paper

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24 × 19.1 cm)

Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The cautious attribution of this study of a middle-aged man to Jan Cossiers, a Flemish painter who left a beautiful series of drawn portraits of his sons, is based on the drawing’s style and an inscription on its verso. An earlier attribution to Van Dyck must have been inspired by the drawing’s exceptional quality and the sitter’s melancholy gaze. Although Van Dyck often employed the same technique of black and white chalk on lightly toned paper, the detail and worked-out modeling here set it apart from his known head studies.

Unknown Flemish Artist

Study of a Standing Man in Armor, ca. 1650

Pen and black ink, brush and gray and brown ink, with white, gray, and yellow gouache, and black and red chalk

16 3/4 × 10 1/4 in. (42.6 × 26.1 cm)

Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge; Gift of The Honorable and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss

This detailed drawing is the most impressive of three studies of armor, all by the same hand and previously thought to be by Van Dyck. Although he regularly represented his military sitters dressed for battle, no related studies of armor by Van Dyck have survived. The rich technique, including colored gouache, distinguishes this drawing from Van Dyck’s portrait studies.

Unknown (probably Flemish) Artist

Study of a Man’s Torso and Hands, mid- to late seventeenth century

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on buff paper

10 × 8 1/4 in. (25.5 × 21 cm)

École Nationale Supérie des Beaux-Arts, Paris

Although an attribution to a French artist has been suggested for this drawing, the pose and costume’s flamboyant character point to a Flemish contemporary of Van Dyck’s. In its focus on the man’s costume and its technique of black chalk on lightly toned paper, heightened with white chalk, the study is comparable to several drawings by Van Dyck also on view in this exhibition.

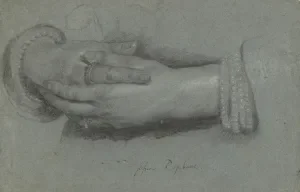

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the Elder (1593–1661)

Study of the Hands of a Lady of the Raphoen Family, 1646 or before

Black and white chalk on blue paper

7 1/2 × 11 5/8 in. (19 × 29.5 cm)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Although hands play a major part in enlivening and conveying expression in Van Dyck’s portraits, very few of his hand studies survive. This sheet is among a group of carefully worked-out drawings that were formerly thought to be by him but have now been reattributed to Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, a Dutch portraitist who had a successful career in London until he was overshadowed in the 1630s by Van Dyck’s arrival.

Peter Lely, born Pieter van der Faes (1618–1680)

Study of a Hand and Drapery, ca. 1658

Black and red chalk, heightened with white chalk, on gray (formerly blue) paper

12 5/8 × 8 3/8 in. (32.1 × 21.2 cm)

Detroit Institute of Arts; Founders Society Purchase, William H. Murphy Fund

Once believed to be a study for the figure of James Stanley, Earl of Derby in Van Dyck’s family portrait on view in the East Gallery, this drawing has since been recognized as a study by the Dutch-born Peter Lely, who succeeded Van Dyck as England’s foremost portraitist. It is close to a gesture in a portrait by Lely of John and Sarah Earle. Although his technique and style recall some drawings by Van Dyck, Lely used red chalk in addition to black and white and drew the hands in a more precise way. As Van Dyck often did, Lely worked on paper that was originally blue.