Checklist

Vase and Two Incense Burners, 1764

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Faux porphyry carved by Jean-François Hermand

Stucco imitating porphyry and gilt bronze

Royal Castle, Warsaw

This set was purchased in 1764 in the Parisian workshop of the sculptor and silversmith François-Thomas Germain. The purchase was made on behalf of Stanislas-August Poniatowski, an art connoisseur and the future king of Poland (r. 1764–95). Gouthière claimed authorship in an undated letter he and the silversmith Jean Rameau boldly wrote to the Polish sovereign to circumvent Germain:

Small Clock with Horizontal Rotating Face, 1767

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Lapis lazuli, agate, gilt bronze, and enamel

Private collection

Inscription on the collar: fait par gouthiere ciseleur doreur / du roy quay pelletier 1767

(Made by Gouthière Chaser Gilder / to the King Quay Pelletier 1767)

See the other Small Clock with Horizontal Rotating Face

Early in his career, Gouthière created a number of models that could be customized for various clients, as this clock and the other small clock have been. The example here is made of semi-precious stones, using lapis lazuli for the column and agate for the covered vase, while the other clock is made of wood originally painted in imitation of lapis lazuli but now covered by a thick layer of dark blue paint.

Small Clock with Horizontal Rotating Face, 1767

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Painted wood, gilt bronze, and enamel

Musée Cognacq-Jay, Paris

Inscription on the collar: fait par gouthiere ciseleur doreur / du roy quay pelletier 1767

(Made by Gouthière Chaser Gilder / to the King Quay Pelletier 1767)

See the other Small Clock with Horizontal Rotating Face

Early in his career, Gouthière created a number of models that could be customized for various clients, as this clock and the other small clock have been. The example here is made of wood originally painted in imitation of lapis lazuli but now covered by a thick layer of dark blue paint, while the other clock is made of semi-precious stones, using lapis lazuli for the column and agate for the covered vase.

Pair of Ewers, 1767

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Gilt bronze

Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh

Inscription on the base: fait par gouthiere ciseleur doreur / du roy quay pelletier 1767

(Made by Gouthiere Chaser Gilder / to the King Quay Pelletier 1767)

Gouthière had been a master chaser-gilder for nearly ten years when, on November 7, 1767, he received the title of gilder to the king “on the basis of testimony we possess as to the intelligence, ability and integrity of Mr. Gouthière, merchant gilder in Paris.” Over the next two months, he completed these two ewers, engraving his new title on the rectangular base of the mermaid-handled ewer. Bronze-makers rarely signed their works, but it was standard practice for goldsmiths and silversmiths to do so.

Pair of Ewers, ca. 1767–70

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Porphyry and gilt bronze

Private collection

The mounts on these two ewers bear many features that recur in Gouthière’s work, among them, the naturalistic chasing of the veins of the leaves, the highly expressive human and animal figures, and the extremely fine stippling used for the textures of the bodies and faces. Also noteworthy is the matte gilding, a specialty of Gouthière’s, on everything but details such as the dolphins’ eyes, the ribbon bows, and the draperies, which are burnished.

Pair of Vases, ca. 1770–75

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Alabaster probably carved by Augustin Bocciardi (1719–1797) or Pierre-Jean-Baptiste Delaplanche

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1832)

Alabaster, green marble, and gilt bronze

Private collection

The seventh entry in the sale catalogue for the Duke of Aumont’s collections consisted of two large, handsome columns of verde antico marble discovered in 1766 near the Temple of Vesta in Rome. On top, each had an alabaster vase described in the catalogue as “interesting” and with ornamentation “of an excellent type . . . perfectly carried out.”

Louis XVI acquired the full set of items. While the columns were kept in the Salle des Antiques at the Louvre, the vases were left in a storehouse for more than twenty years. In 1793, they were transferred to the Muséum du Louvre, but they clearly fell out of favor: in October 1797 — on orders from the Ministry of Finance and to cover the costs of establishing the new museum — these two alabaster vases “of mediocre quality” were sold. The fairly low price of the estimate was clearly determined by the defective alabaster and not by Gouthière’s mounts, the originality and execution of which are almost without equal. In particular, the laurel leaves so realistically capture the density and variety of a branch of blossoming laurel that they look as if cast from nature.

Knob for a French Window, ca. 1770

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

After a design by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736–1806)

Gilt bronze

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Gouthière made this knob for one of the most lavish French eighteenth century buildings, the pavilion of Louveciennes, designed by the architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux for Madame Du Barry, Louis XV’s mistress.

Pair of Vases, ca. 1770–75

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Granite probably carved by Augustin Bocciardi (1719–1797) or Pierre-Jean-Baptiste Delaplanche

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Green granite, bardiglio, and gilt bronze

Private collection

It was probably an artisan working in Paris under the direction of the architect François-Joseph Bélanger who carved these rare and original vases, with bottoms in the form of a cul-de-lampe, echoing the knob forms on the tops of the lids. Unable to stand, they had to be supported by a mount, which was created by Gouthière after designs by Bélanger.

Two Vases, ca. 1770–75

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Porphyry carved in Rome in the eighteenth century

Red porphyry and gilt bronze

Musée du Louvre, Paris

A passionate collector of hardstones, the Duke of Aumont was particularly fond of marble, granite, porphyry, serpentine, jasper, and agate, which the neoclassical tastes of the time had brought back into fashion. When possible, he obtained them in Italy, which was generally thought to have the finest stones.

For these vases, which had been carved and polished in Rome, Gouthière was commissioned to produce gilt-bronze mounts. His intervention was minimal; he created extremely simple bases finely chased with friezes of interlacing motifs and strings of pearls.

Two Pot-Pourri Vases, ca. 1770–75

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Chinese porcelain, eighteenth century

Hard-paste porcelain and gilt bronze

Musée du Louvre, Paris; transfer from the Mobilier National, 1901

Gouthière’s name appears in the 1794 inventory of the estate of Jean-Baptiste-Charles-François, Marquis of Clermont d’Amboise. The marquis may have commissioned these vases from Gouthière in the early 1770s before he left for the court of Naples, where he was ambassador from 1775 to 1784. This reference, combined with meticulous examination, allows for confirmation of the attribution.

The swans emerging from large shells are equally impressive in their naturalism. The feathers on the large birds’ necks and breasts are created by chased stippling of various sizes, along small irregular grooves probably cast in the mold; they contrast with the upper part of the shell, which is a slightly bulging fan shape with alternating matte and burnished ribs. The beaks identify these birds as mute swans, a species common in Europe. Their eyes express fury: about to attack, they unfold their wings on either side of the porcelain pots. Their mood is also indicated by their slightly open beaks, which are edged with a burnished line.

Pair of Firedogs, 1771

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Gilt bronze

Private collection

For the Grand Salon Carré in Mme Du Barry’s new pavilion at Louveciennes, Gouthière supplied two pairs of firedogs to complement the two chimneypieces of white marble and gilt bronze. According to Gouthière’s invoice, he presented several drawings and models of firedogs to Du Barry, one of which was found to be “to Madame’s taste” and was used to make the sets of firedogs. The other pair is at the Detroit Institute of Art.

Vase, ca. 1775–80

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Porphyry possibly carved by Augustin Bocciardi (1719–1797) or Pierre-Jean-Baptiste Delaplanche

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Green Greek porphyry and gilt bronze

Musée du Louvre, Paris; transfer from the Mobilier National, 1901

Here, Gouthière created elegant mounts in the shape of two seated female figures, looking in opposite directions. Though at first glance they seem identical, these small figures were made from two separate molds. One, representing a female satyress, wears a crown of ivy and holds a branch of the same; the second figure, a mermaid covered in drapery, wears a crown of laurels and clutches a laurel branch.

Vase, ca. 1775–80

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Porphyry possibly carved by Augustin Bocciardi (1719–1797) or Pierre-Jean-Baptiste Delaplanche

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Green Greek porphyry and gilt bronze

Musée du Louvre, Paris; transfer from the Mobilier National, 1901

This vase, similar in shape and material to another vase in this exhibition, fetched a much lower price at the sale of the Aumont’s collection. It was sold to Louis XVI, who was prepared to spend three times more for the vase with female figures. Clearly, the cataloguers for the sale thought this vase was of inferior quality since their assessment was less laudatory.

Pair of Incense Burners, ca. 1775

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthièr (1732–1813)

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Japanese Kakiemon porcelain, eighteenth century

Hard-paste porcelain, porphyry, and gilt bronze

Private collection

At the time of his death in April 1782, the Duke of Aumont owned more than four hundred pieces of oriental porcelain, which, along with his hardstone pieces, were the pride of his collection. Eight of them received mounts by Gouthière. Here, as elsewhere, Gouthière’s gilt bronzes enhanced and transformed already highly prized objects.

Capital for a Porphyry Column, ca. 1775–80

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Probably after a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Gilt bronze

Musée du Louvre, Paris; Founding collection

This capital epitomizes the relationships Gouthière had with the most inventive architects of the time, the purity of the neoclassicism he developed under their guidance, and the extravagance of the objects he created for his most illustrious patrons. The capital was made to crown an antique porphyry column owned by the Duke of Aumont, who, during the second half of the eighteenth century, assembled a prestigious collection of marble columns and hardstone vases. These objects were highly sought after by the most refined collectors in Europe since the Renaissance.

François-Joseph Bélanger, who probably designed the capital, was inspired by an antique column that also belonged to the duke. A large marble ball (now lost) was originally placed on top. Today, only the preparatory drawing for the catalogue engraving gives an idea of the superb contrast of colors between the gilt bronze and the various marbles used.

At the sale of the Duke of Aumont’s collections, the complete column was acquired by Louis XVI for the enormous sum of 6,999 livres (about twice the annual salary of a teacher). The king purchased it for the future “Muséum” du Louvre (now the Musée du Louvre), which opened in 1793 and still houses the column and capital.

Pair of Firedogs, 1777

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Gilt bronze and blued steel

Musée du Louvre, Paris; transfer from the Mobilier National, 1901

In 1777, Gouthière was asked to create several items for Marie Antoinette’s small Cabinet Turc at the Château de Fontainebleau. This prestigious commission included these firedogs, a chimneypiece, a chandelier, a pair of wall lights, and a shovel and tongs, the handles of which featured “African heads.” Only the firedogs and chimneypiece (still in situ at the Château de Fontainebleau) have survived.

Pair of Wall Lights, ca. 1780

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Gilt and patinated bronze

Musée du Louvre, Paris; gift of the Société des Amis du Louvre, 2002

These wall lights were intended for the large gallery-salon of the Duchess of Mazarin’s hôtel particulier. From at least the mid-1770s, Gouthière had been proposing two sizes (small and large) of poppy wall lights to his clients. However, these differ from the other models by the extreme richness of the poppy branches with numerous flowers, almost every one distinct, features that increased both the time and cost of making the lights. Some of the flowers are only buds while others are fully opened to form the candle holders.

Side Table, 1781

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Marble supplied and carved by Jacques Adan

After a design by Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin (1739–1811) working under François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Blue turquin marble and gilt bronze

The Frick Collection, New York; Henry Clay Frick Bequest

This table was in the workshop of Gouthière (with the gilding yet to be completed), when the Duchess of Mazarin died on March 17, 1781. What subsequently happened to it and for whom Gouthière finished it is not known, but it remains one of the artist’s masterpieces. The mask at the center of the entablature is one of the most beautiful faces ever created in gilt bronze.

Pair of Firedogs, 1781

Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Modeled by Philippe-Laurent Roland (1746–1816) after a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Gilt bronze

Mobilier National, Paris

Two renowned sculptors worked in collaboration with Gouthière on the fireplace for the large salon of the Duchess of Mazarin’s hôtel particulier on Quai Malaquais. For the firedogs, Philippe-Laurent Roland modeled the two eagles of Jupiter — with their wings outspread and each holding a thunderbolt and a salamander — before the groups were chased and gilded by Gouthière. For the chimneypiece (now lost), Jean-Joseph Foucou modeled the two large figures of satyresses, which were then chased and fully gilded by Gouthière.

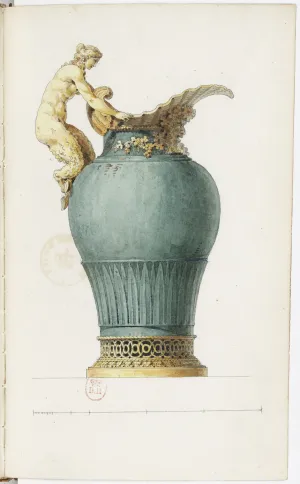

Preparatory Drawing for the Engraving, Representing a Ewer from the Duke of Aumont’s Collections, 1782

Pierre-Adrien Pâris (1745–1819)

Pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper

In Catalogue des effets precieux qui composent le Cabinet de feu M. le duc d’Aumont. Par P. F. Julliot fils et A. J. Paillet (December 12−21, 1782)

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Written by Philippe-François Julliot, a well-known merchant of luxury goods, and the painter Alexandre-Joseph Paillet, the catalogue for the estate sale of the collections of the Duke of Aumont included thirty engraved plates. The preparatory drawings for these engravings were made by the architect Pierre-Adrien Pâris, who had worked for the duke in the 1770s, decorating his hôtel particulier on Place Louis XV in Paris. Upon Aumont’s death, Pâris was summoned to appraise the unfinished gilt bronzes still on Gouthière’s premises.

Pâris made two additional drawings that were not engraved (including the one above and the one reproduced at the inset) that illustrate now lost objects by Gouthière. This watercolor represents one of a pair of celadon porcelain ewers, with gilt-bronze mounts by Gouthière, that were sold at the duke’s sale to an individual named “Abraham.” They were auctioned again two years later.

The illustration below represents an urn (from a pair) said to be in “lapis-colored old porcelain from China” and ornamented with a gilt-bronze mount by Gouthière. The catalogue states that they are “as precious for the perfection of their form and their color as they are for the ingenious taste of their ornamentation and the merit of their finish.” Unsurprisingly, these refined objects were acquired for Marie Antoinette.

Pair of Vases, 1782

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

Chinese Celadon porcelain, eighteenth century

Hard-paste porcelain, porphyry, and gilt bronze

Musée du Louvre; transfer from the Mobilier National, 1870

At the time of the Duke of Aumont’s death, Gouthière had nine items in his workshop including this pair of vases (originally Chinese garden seats) that had not yet been delivered to his greatest client and patron. However, he managed to complete the mounts before the sale of the duke’s collections, when the two vases were acquired by Louis XVI for an astonishingly high sum (7,501 livres).

Pair of Candelabra, 1782

Gilt bronze by Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

After a design by François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818)

One vase, Meissen factory porcelain, ca. 1720; the other, a later replacement

Hard-paste porcelain and gilt bronze

The Frick Collection, New York; Gift of Sidney R. Knafel, 2016

These candelabra, among Gouthière’s last commissions for the Duke of Aumont, are a true tour de force. The extremely detailed chasing lends a naturalistic appearance to the swirling ivy and grapevines decorating the vases’ shoulders, as well as to the individual pomegranates, pears, and other fruits that spill from the cornucopias that form each candleholder. At the same time, the rough texture of the goats’ ridged horns contrasts with the silky appearance of their wool.

Pair of Ewers, ca. 1785

Gilt bronze attributed to Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813)

Chinese porcelain from the Kangxi period (1662–1722)

Hard-paste porcelain and gilt bronze

Private collection

In the 1780s, Gouthière made the gilt bronzes for the chimneypiece of the Salon des Nobles in Marie Antoinette’s apartment at the Château de Versailles and for that of her foyer at the Paris Opéra. During the same years, he probably made the gilt-bronze mounts for this pair of ewers, known to have belonged to Marie Antoinette. No document has been found to confirm their attribution, but the expressiveness in the female and goat heads combined with the naturalistic finish on the various grapevines and leaves are characteristic of Gouthière’s work.