Audio

Listen to a tour of this exhibition by Robert Fucci, Guest Curator, and Aimee Ng, the Frick's John Updike Curator.

Transcript

Vermeer’s Love Letters | Audio Tour

Speakers: Aimee Ng and Robert Fucci

Aimee Ng: Welcome to Vermeer’s Love Letters, the first exhibition here in the Frick’s new Ronald S. Lauder Exhibition Galleries. There are about three dozen Vermeer paintings known in the world today, and we are lucky enough to have three of them in the Frick’s collection (you can see the other two Frick Vermeers in the South Hall of the museum).

This special exhibition was inspired by one of the Frick’s Vermeers—the largest painting here in the middle, Mistress and Maid—which was the last painting that the museum’s founder, Henry Clay Frick, acquired before his death in 1919. On either side of it are two extraordinary loans from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, all three of these paintings centered on the same theme of a woman reading, writing, or receiving a letter in the company of her maid. And how differently the artist treats this motif in the three works, in action, perspective, mood, and even the size of the pictures.

This is the first time that all three of these related works are shown together in a single gallery. Here is Rob Fucci, guest curator of this exhibition, who will tell you more.

Robert Fucci: These paintings all turn on the theme of the exchange of letters, most likely love letters, and ones for which there is obviously a great deal of concern, in terms of courtship, desire, heartache, or potentially heartbreak. Vermeer is seeking here to explore a narrative moment in which that expectation or outcome is at its height. Regardless of the love theme, it is this moment of anticipation which he uses to create the carefully crafted drama in these paintings. We can all relate to it today, in fact, in those moments just when we receive an important message that has potentially important consequences, and we already know as much just before we read it. Vermeer quite brilliantly plays on what was, and remains, one of the most human emotions: uncertainty over outcomes.

We know of six paintings by Vermeer that treat the love letter theme, with three depicting solitary figures of women, and the other three, those featuring in the exhibition, handling the interaction between a young woman and her maid. The figure of the maid plays an important role in these works. She is the go-between who brings and delivers the messages. It was quite normal at the time for servants to deliver messages to individuals who were located nearby, in the same city for example, rather than the long-distance post, which was a separate service. In the context of the love theme, the maids also imply a certain degree of confidentiality, even secrecy. The maid also provides a certain amount of narrative motion, you could say, since the interactions between her and the mistress in these paintings can be quite revealing.

One of the most significant aspects of these paintings, from a seventeenth-century point of view, is that Vermeer uses what would then be called “modern figures”; in other words, figures that would be recognizable to viewers as ones belonging to their own time. This is quite distinct from the central aims of most European artists at the time to sensationalize or moralize narratives based on biblical or mythological texts. The recognizability of these figures for their earliest viewers in the seventeenth century is precisely one of the factors that makes them so forward thinking. Vermeer sought highly relatable moments of emotional frisson in these works.

Vermeer painted these works in an era of greatly increasing literacy, especially in the Netherlands, and at time when letter writing was enormously popular. It was also a time when courtship through the exchange of love letters arguably had a liberating impact on the ability of women to develop love matches more independently from their parents. One of the functions of the maids in these paintings, therefore, is to signal to the viewer a certain degree of confidentiality even within the household.

One of the most remarkable aspects of these three paintings is just how creatively Vermeer approached the theme in various ways, both in terms of composition and content. By looking more closely at the viewpoints and clues in each one of these works, we can better understand his aims and what is at stake in each work.

Mistress and Maid, The Frick Collection:

This is the largest of the three works in the exhibition, and likely the earliest that Vermeer painted that treats the love letter theme with a maid involved. The size of the composition is significant in that the figures approach life size, and Vermeer has placed us quite close to them. The maid extends her hand with the letter as much to us as to the young woman, putting us in an analogous and sympathetic position with her just before she opens the letter.

There is a great deal of nuance in the interaction here. The young woman has, with the gentlest of touch, placed her hand to her chin. We cannot see her expression, but it is certainly one of curiosity and anticipation, and perhaps even concern. The maid, for her part, is saying something, no doubt imparting some bit of intelligence or detail she gathered in her role as go-between.

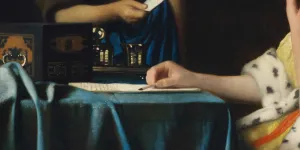

One of Vermeer’s most ingenious touches in this painting, in my opinion, is the delicate way he has the young woman hold the pen at its top end, hovering just above the paper. It is a grip of thinking, not of writing. She was in the process of pondering her words when the maid came in from behind the curtain to deliver the letter.

The curtain is difficult to see now since the painting has darkened, but it was once green. It, too, serves an important function, since it signals this woman’s need for privacy as she writes this letter. Curtains were often used as space dividers in this era before houses tended to have walled rooms designated for individual use. By suddenly appearing from behind the curtain, the maid seems to have caught the young woman unaware, interrupted in the process of writing a letter just as she receives one—a very active affair indeed.

The Love Letter, Rijksmuseum:

While the smallest of the three works in the exhibition, the composition of this famous painting from the Rijksmuseum is one of the most inventive in Vermeer’s entire oeuvre. We are staged, as viewers, quite literally within the painting. Less than half of the canvas is taken up with the scene itself, and the rest is devoted to demarking a darkened space that is either a passageway or storage area, replete with crumpled sheet music on a chair, and a barely discernable map hung on the wall to the left with streaky stains beneath it. The intent here is clear: we are voyeurs, unwitnessed as we watch the exchange take place.

The mood here is set in a lighter register than in the other paintings. The maid, with her hand on her hip and smile on her face, appears to be reassuring the young woman to whom she has just handed the letter, whose own expression indicates that she is in need of reassurance. Reinforcing the maid’s expression is the painting in the background depicting a fair-weather seascape, a classic trope in Dutch visual culture of a love affair proceeding smoothly.

This is one of few paintings by Vermeer in which he shows a young woman practicing her instrument rather than playing in mixed company. Playing music often went hand in hand with courtship in this era, in which the display of skill or talent was not only a concern, but also a search for harmonious interaction among the participants, both literally and figuratively, as a means of foreseeing the nature of any potential match.

Woman Writing a Letter, Dublin:

The most notable feature of this painting is the act of writing itself. Vermeer superbly imparts a sense of her concentrated energy, as she writes with a lowered head her collected thoughts. The maid is given equal visual weight in this painting, as in the other ones in the exhibition, but this time she waits patiently to one side. Her folded arms and gaze out the window, along with her position just behind the young woman, suggest that she more than willingly gives her the space to focus and write. The maid’s pose is beautifully suggestive and unprecedented in Dutch art. Her stillness has a way of creating a sense of time within the image, as it counterbalances the movement and energy of the young woman writing with whatever emotions might be at play.

One of our only clues as to the emotions at play is the set of objects scattered on the floor in the foreground, which appear to be a crumpled letter (albeit folded), a stick of sealing wax, and a red wax seal. Has the young woman just read the letter, discarded it, and is now writing a reply? Vermeer likely desired to leave it to the viewer’s imagination in this case.

The scene depicted in the prominent painting in the background is the Finding of Moses, in which the pharaoh’s daughter finds the infant Moses in a basket floating down the river and rescues him, despite her father’s decree to kill all Hebrew children. She required the trust of her handmaidens, who were helping her bathe at the time, in order to save Moses. The most plausible interpretation of Vermeer’s use of this painting within the painting is to draw an analogy with the trust in which this maid is held as well.